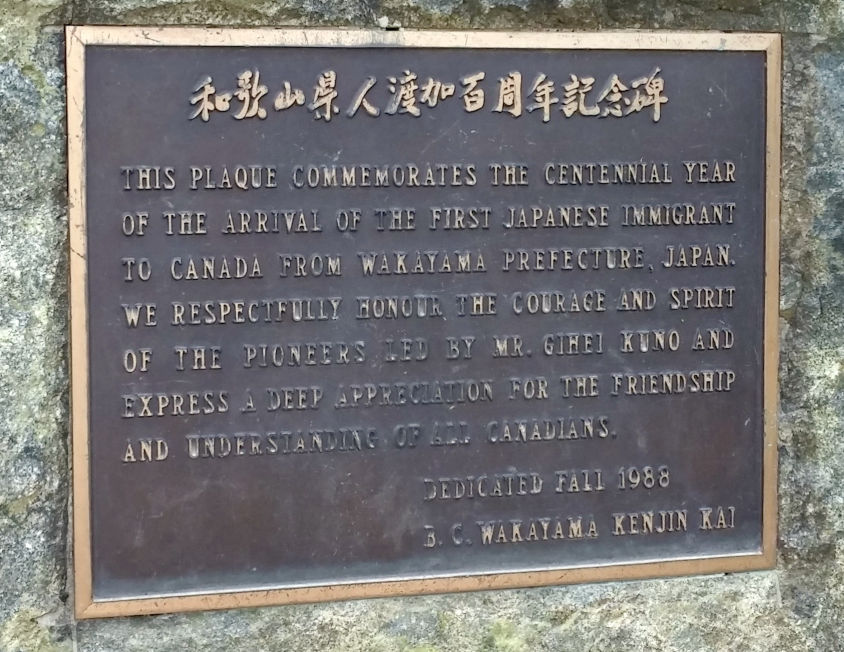

Gihei Kuno’s enthusiasm after seeing the abundance of fish along the Fraser River in 1887 must have been contagious. He was followed two years later by fifty men from his village in Mio and eventually two hundred and fifty others joined them in Steveston. Of the coastal villages in Wakayama, the largest percentage of immigrants were from Mio that had a population of approximately four hundred families. An estimated two hundred and thirty families were fisher folk and one hundred and twenty were farmers. Many fisher folk left Mio due to the loss of fishing grounds, the collapse of the sardine fishery in the nineteenth century, and the lack of land ownership. Immigrants to Steveston also came from Shimosato, Temma, and Takeshiba, but they numbered only approximately fifteen since most of the fisher folk in these villages also owned rice fields that helped to sustain them.

Steveston also became home to immigrants from villages outside of Mio, including Takui and Ao, as well as from smaller communities in Wakayama.