It was the month of April 1942. I was busy at my store in Richmond, when one of my father’s friends brought the news of our evacuation. All Japanese, naturalized citizens or Canadian-born, were to be moved 100 miles from the coast. I was 16 years old at the time and was asking a great deal of questions. Why us? What did we do to deserve such punishment? I am a Canadian-born citizen!

(Tamiko Haraga, internee in Greenwood – Yesaki, 2003)

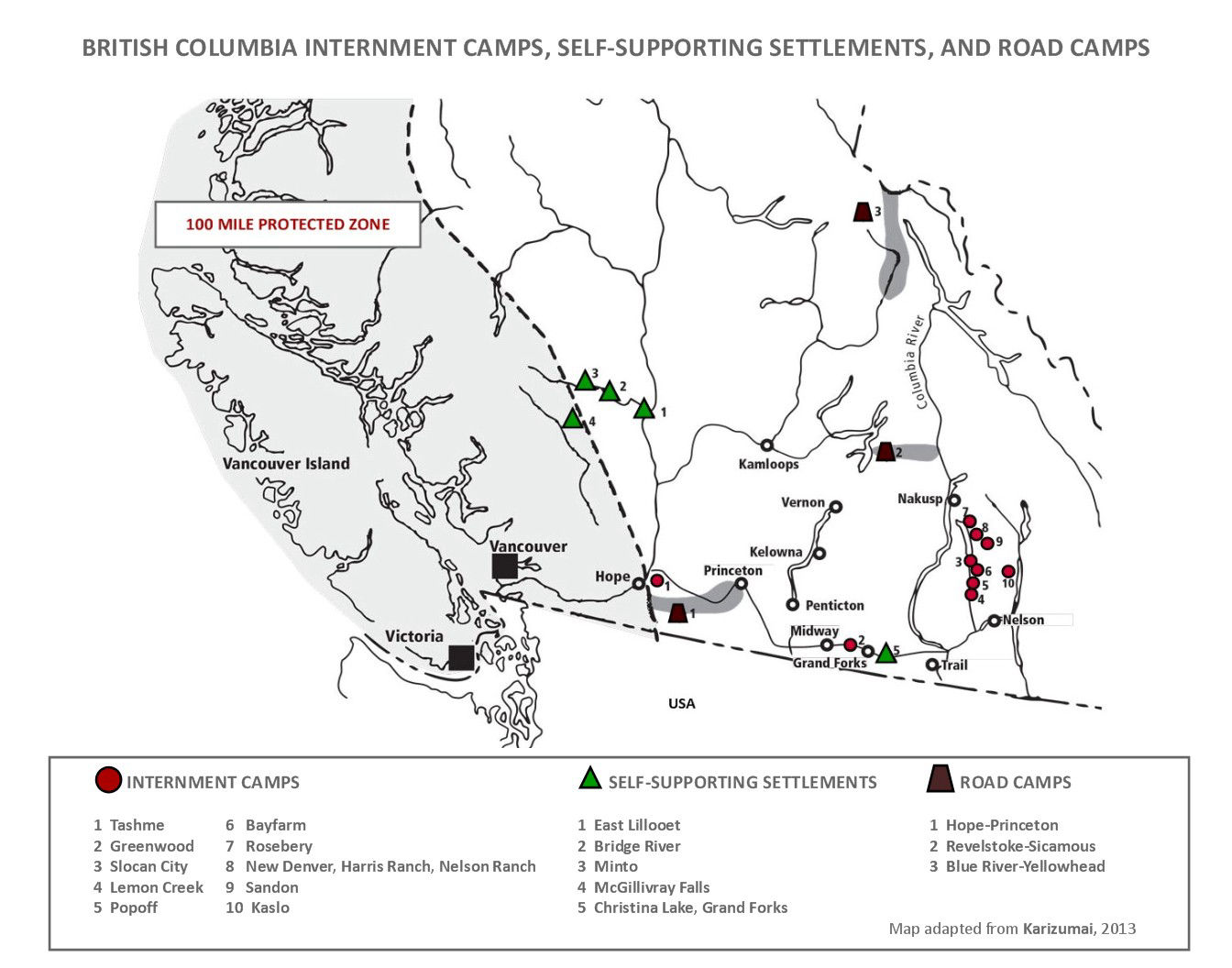

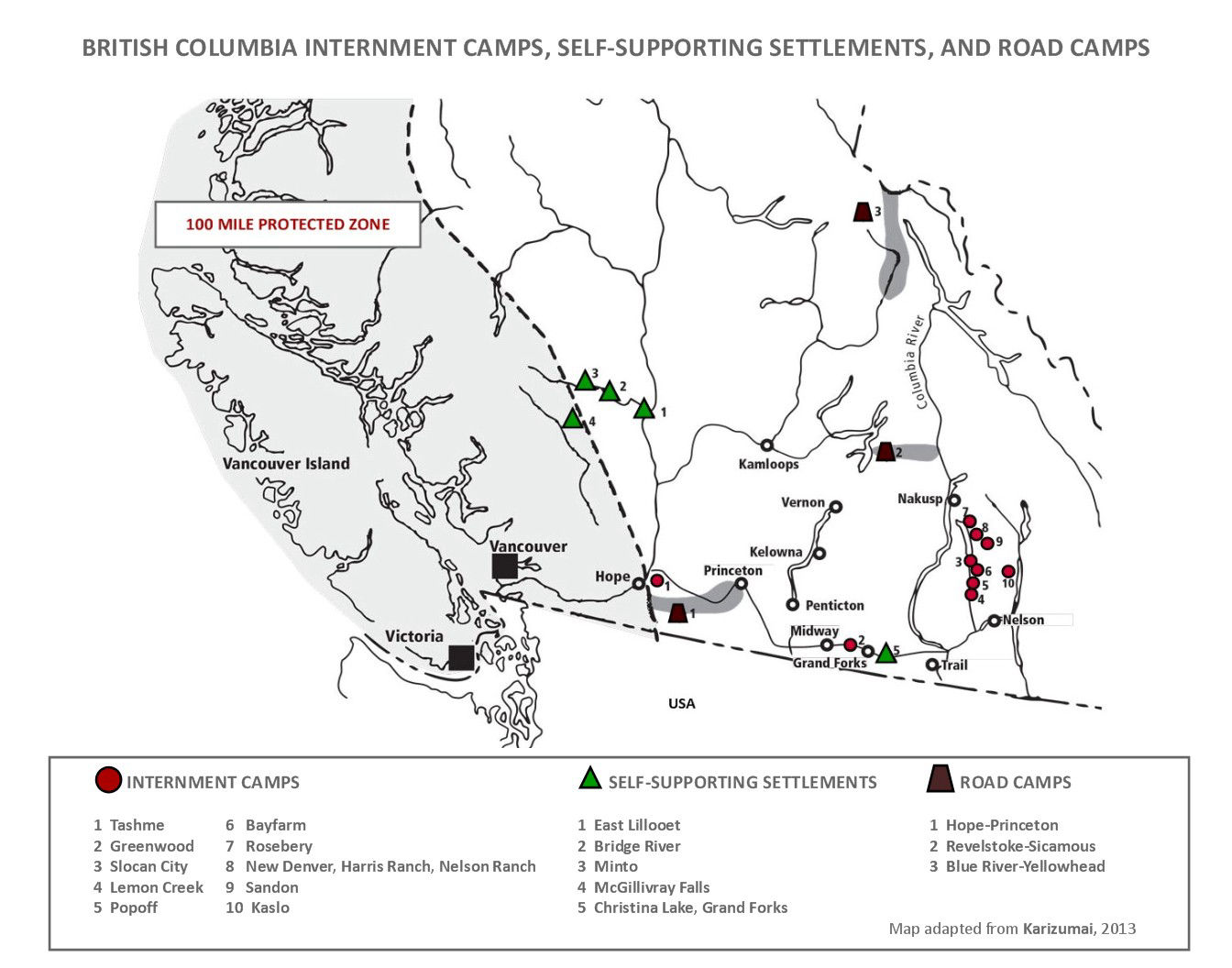

In 1942, close to 21,500 Nikkei were dispersed from the protected zone to various locations across Canada, but primarily to remote areas in B.C.

Internment Sites

The B.C. Security Commission (BCSC) chose six internment sites and some surrounding towns in B.C. to intern the Nikkei. The ten destinations were located in small communities or on vacant lands. By April 1, 1943, the population of the internees reached a high of 12,177.

Slocan Valley Area (sites: Slocan City, Lemon Creek, Bay Farm, Popoff Farm) 4,764

Tashme (largest and last site to be built) 2,624

New Denver (sites: New Denver, Rosebery) 1,701

Greenwood 1,203

Kaslo 965

Sandon 920

Self-supporting Sites

In addition to the internment sites, there were seven self-supporting settlements or independent schemes authorized by the B.C. Security Commission (BCSC). These locations, also referred to by the Nikkei as kanemochi mura, were the destinations of wealthier Japanese Canadians from Vancouver and Steveston who chose to pay for all of their expenses including housing, education, and transportation. There were 1,161 Nikkei in these voluntary sites by October 31, 1942.

Christina Lake 109

Bridge River 269

Minto City 322

East Lillooet 309

McGillivray Falls 70

Swing Crew (Okangan) 63

Assiniboia 19

The BCSC also issued special permits to several hundred Japanese individuals and families from Vancouver. They were sent to farms in B.C., such as Grand Forks and areas north of Kamloops, where permanent employment was guaranteed.

Road Camps

During the March-June 1942 period, 2,161 Japanese nationals and physically fit men were sent to four key road building projects in B.C., Alberta, and Ontario. While the criteria was those aged between 18 and 45 years old, some of them were 17 and others over 70. As of October 31, 1942, the number of men decreased to 945 as many were permitted to join their families living in internment camps. The highest number of men working on the Blue River-Yellowhead highway project, for instance was 1,561 in April 1942. Six months later the population decreased by over 80%.

Blue River-Yellowhead project (17 camps) 271

Revelstoke-Sicamous project (5 camps) 346

Hope-Princeton Highway project (6 camps) 296

Schreiber-Jackfish project (Northern Ontario, 4 camps) 32

Due to the Alberta sugar beet farmers’ severe labour shortage, the

B.C. Security Commission (BCSC), the Government of Alberta, and sugar

beet associations negotiated to relocate almost 2,600 Nikkei from B.C.

to southern Alberta. Shortly afterwards, the same arrangement was made

in Manitoba.

Despite the harsh living and working conditions on these

farms, the move represented an opportunity for the Nikkei to ensure that

their families remained together and to be reunited with men who had

been sent to road camps. By November 1942, 3,991 Japanese Canadians had

left B.C. to move east.

With their farming knowledge and experience

from working in the Fraser Valley and Delta, the contribution of the

Nikkei to the sugar beet industry was invaluable. According to the BCSC,

there was “little doubt that unless Japanese labour had been recruited …

the great bulk of the crop would not have been seeded, with the

consequent loss to Canada of many thousands of tons of beet sugar.”

Alberta 2,588

Manitoba 1,053

Ontario (men only) 350

Ontario Prisoner-of-War Camps

There were approximately 800 Nikkei men detained by

the RCMP in Vancouver for their opposition to the measures taken by the

federal government against those of Japanese ancestry. By October 1942,

412 and 287 men were sent to Angler Camp and Petawawa Camp respectively,

while 111 remained in detention.

Other Work Sites

The BCSC approved the movement of 439 Nikkei to work

on three significant industrial projects: the sawmill in Westwold (77),

the sawmill and logging operation in Taylor Lake (180), and the Ontario

Industries logging business (85). There were an additional 97 Nikkei

employed in other industrial projects.

The BCSC also granted special work permits to 1,359 Japanese Canadians to fill approved jobs in Canada and the Yukon Territory.